Already Dead: A California Gothic

denis johnson, northern california, and a myth where my head should be

“They had myths instead of heads.” I read this line two weeks ago and it has come to me everyday in the fourteen days since. It keeps echoing, bubbling up to the surface of my thoughts in those beautifully blank auto-pilot moments, those moments when your brain is clear and ready for something striking and mysterious to sink its teeth into. It echoed back at me as I washed my hair, as I picked lemons from the tree, it whispered to me, They had myths instead of heads. As I fried steaks for dinner, as I scrubbed the pans, They had myths instead of heads. I’d wake up to pee in the middle of the night and think, sleepily wandering down the dark hallway, They had myths instead of heads. My fixation was amplified because the line is from a nonfiction piece, and as I kept reading, more of these brilliant little sentences kept stacking up. We don’t often think of journalism as having heart-stopping lines the way other prose does, but Denis Johnson stopped me in my tracks a few more times while I was reading Seek.

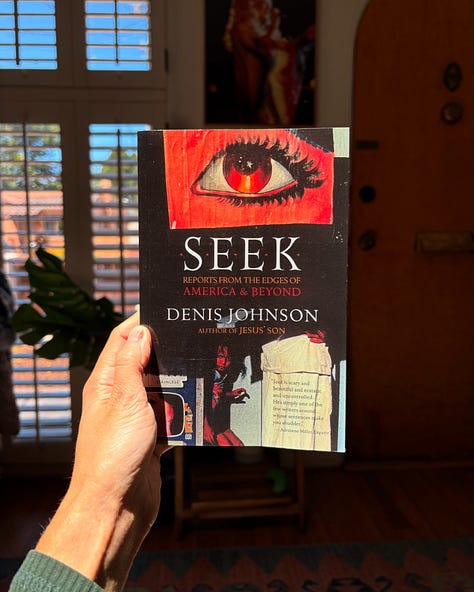

I’ve been a fan of Johnson for a long time, but only through his short stories. He’s prolific, so I won’t waste time saying what’s already been said because I’m here to try to say something new. I had a hankering for good journalism recently, so I went searching for more nonfiction to scratch the itch. I worked backwards from one of my favorite books, Pulphead by John Jeremiah Sullivan, and the internet served me up Seek by Denis Johnson. I didn’t know he’d ever published a nonfiction collection, so I smashed that Buy Now button like a rat in an experiment pulling a lever for cocaine. Seek was in my hands within 72 hours.

Reader: I devoured it. I inhaled it. I swallowed that book whole like a boa constrictor. My favorite piece is Three Deserts. In it, he writes about three of his experiences spent, where else, but in different deserts. His time spent war reporting in Kabul melts into a profile of a cult in the New Mexico desert and the piece ends with the weeks he spent trapped in a hotel in Saudi Arabia while the Gulf War kicked off outside. This man had tales to tell! I wanted more of them. I dug a little deeper and came across a novel published in 1997 called Already Dead: A California Gothic. Its plot is based on a long poem. There were only 40 reviews on Amazon and not much published by major magazines or newspapers. Its wikipedia is as empty as the deserts Johnson writes about. All that appears on it is a short plot summary and two reviews: one was a complete hatchet job saying the novel was, “inept, repugnant, and virtually unreadable” and one (only slightly) more positive assessment. I was curious. I’m always curious when someone hates something so viscerally, but more importantly than my morbid fascination with a “virtually unreadable, repugnant” book, I had been waiting a long time for something like this.

Whenever I’ve wanted California Gothic, and there have been many a time, I’ve been handed LA Noir. If I narrow my criteria down to Northern California, then I get San Francisco Noir. There’s overlap in the genres, no doubt about that, but Noir generally focuses on a specific crime and usually relies heavily on the ambiance of a city for its mood. Think rain-splattered sidewalks, flickering neon signs for dive bars and 24-hour laundromats reflected in puddles on the asphalt, and a grizzled detective chain-smoking as he gazes regretfully at a frayed picture of his ex-wife. Noir works with the harsh anonymity of city life, its dark underbelly, the femme fatales, the antihero. The Gothic shares a lot with Noir. It sings a similar song but in a different key.

The Gothic is the bloody metaphysics of the pumping human heart made decipherable, all that’s felt within our flesh and guts and our subconscious. We have so little control over these things, so we tell stories about their power and their mystery. The Gothic engages deeply with the rural, with the natural world, and with the supernatural. Old mansions are decaying and there are family curses going back generations. There’s plenty of tragic local folklore and melancholy weather, with a smattering of blood feuds and ritual sacrifices. Both genres explore moral decay and dark obsession, but the Gothic is more emotionally driven, more internal. The Gothic is not interested in finding literal justice the way Noir is. In Gothic stories, it’s about finding peace.

Already Dead takes place in the small Northern California town of Gualala. The story is ostensibly about the son of a wealthy land-developer, Nelson Fairchild Jr. He’s the classic rich kid fuck-up who could never please his Daddy. He grows weed illegally and, oh yeah, he wants to have his wife murdered. Now, that’s a fine plot on its own. I wouldn’t kick it out of bed. But there is so much more to the story than that. I feel bad for whoever had to write up a synopsis, I sure as hell couldn’t sum this book up succinctly. That’s why we’re here.

The faith is gone from those places, the heart-power of flight, this I believe. But come to California. Come to these canyons if you want to be driven by sacredness into the air. If you dream of the true, clear silences, if you want those silences to sing: Come to California.

The world of Already Dead is full of foggy beaches and ancient redwood trees. The weather doesn’t follow logic so much as an oblique emotional mysticism, be it drought, flood, or fire. Everything is alive but moves in the shadows, in the depths, meandering stealthily among the mist, setting itself free where the ocean meets the sky. The forests breathe quietly, their exhales sweeten the air. The tide crashes in the distance, echoing the rhythm of your pulse as you tumble through the looping waves of dreams. This is a place of rural psychics holding seances in cabins, illegal pot gardens maintained under the cover of moonlight. The anarchists are hidden in the hills and lost teenagers obliterate their cerebellums on drugs in the dry golden scrublands. You can feel the cosmic horror prickle the back of your neck, half-dead mermaids migrate from the Pacific to the Milky Way. The animals are quiet and all knowing, palomino horses graze in fields and gaze seaward, big nostrils taking in the salt. Even the murderers are in on the vibes, believing they’re sending their victims over to the next realm. Pastures are dotted with clusters of sheep and punctuated with peacocks purchased decades earlier by wealthy eccentrics, left to breed and roam in the grasslands and hills. The fog reflects reality itself: diffuse, ever-shifting, inconsistent. We are dealing in a world of metaphor and metaphysics. There’s a point in the book where it hits you: We have crossed over.

Offshore, the small lights of fishing boats float in the dark: if you let them, they’ll start to symbolize everything…

There is so much beauty and so much darkness in this Nietzschean fever dream. It’s like I conjured it, truthfully. This mad, violent, glorious fusion of the mystical and criminal elements of True Detective and Twin Peaks, with the small towns I’ve known from my earliest childhood memories serving as the setting. Eternal recurrence is the major beating heart of it all. Once you discard logic and accept a belief in a universal poetry, the story opens up like the sky after a storm into a cosmic fable of existence, good vs. evil, and what that means for all of the lost souls who populate these foggy cliffs and dense woods.

Will you believe me please if I tell you that the nameless whole of me had arranged all of this- just to break my own heart? A man walks into the room where his wife lies murdered. And he begins to realize that only this could have saved him. That this, the worst thing he could’ve possibly done, was his only hope.

The souls, oh, they’re so lost. The cast of characters in this book is big but not overwhelmingly so. We never hear from a female point of view, but I’m going to defend that. There has been a lot of discussion about how men write their female characters, and rightfully so, but Denis Johnson has always inhabited a unique point on the alignment chart of that argument for me. His men are the wanderers, the fools, and the jesters, helpless to their impulses, being blown through their lives by the wind and thinking it’s their own momentum, letting the elements and other people make their choices for them and being angry at the results. But his women! His women are the witches, the oracles, and the psychics. They’re the ones in tune with the earth beneath their feet and the moon above their heads. Nietzsche said, “Truth is a Woman.” He says that because, like a woman, the truth does not want to be exposed or revealed. She has her reasons for not showing us her reasons. Truth is a Woman because philosophers are desperate to find it, but they cannot understand it, and it remains elusive. Like women. They didn’t understand them and didn’t know where to start. (At least these guys knew where they stood and had a sense of humor about it.)

Johnson’s women feel like Nietzsche’s. On one page, he comes right out and says, “I’ve made a world in which the men are sinister and the women completely opaque.” They’re the ones conducting the seances, engaging with the supernatural. Their motives aren’t clear, they keep their hearts under lock and key. Yvonne, a friend of Nelson’s wife, considers herself a medium and channels not only the dead, but demons as well. While the helpless fools of Gualala have been running in circles of violence and betrayal, Yvonne and the other women have been taking the temperature of the astral plane. This is what they found:

“We’re talking about a failure of perception that amounts to total spiritual blindness and soul-sickness. This person compounds his basic error by believing that the universe started with his birth and ends with his death. If he believes in reincarnations, he believes in reincarnations of the whole universe. That eliminates karma, relearning, and the law of compensation- since each universe is a closed system, bounded by his lifetime. Through all these universes one after another, the only thread, the only continuity, is his identity. And the thread is endless. He has no destiny.”

“And that’s actually true?”

“It’s as he makes it. He’s condemned himself to an unimaginable interval on the current plane.”

“To hell with him, then. But there are two others, two men, out to kill me.”

“And so they will. But they’re not important.”

“I beg your fucking pardon.”

“They’re merely completing a design you began- you yourself began- in an earlier existence. You killed in a previous era, in this one you experience the other side of that. The lesson begun in one life is finished in another.”

Aside from the plot and themes of the book being so poignant, I love it on a sentence by sentence level. My copy is underlined and highlighted to hell and back, which makes sense considering this all started because I was enraptured by the way Denis Johnson puts words together. They had myths instead of heads.

Immaterial and unaware, you walked out without clothing yourself. Stood on the vermillion beach stark naked and invisible, the boardwalk’s clanks and whooshes and screams and music blown near and far on the wind. They’re paying in strange coins to ride the hurling fever train, rolling up to heaven on the ferris wheel, boys and girls released from life and dragged back down, G-force flattening their orange and purple mohawks, mouths like wounds- it’s terrible when somebody laughs, more obscene and revealing than anything they could say with words. Past the boardwalk and onto the street, the gauntlet of shops and beachside people, the quantum dregs, the never-ending pavement in their sighs, and always that music: dark rock. And you kept going, beyond the seaside part of town. Homes of stucco in the ashy twilight, the street no longer dabbed with sand. Past the edges, way way past, out into the big place east of town, they call it America. Through vandalized areas, you wandered like a voice…

“You wandered like a voice…” I read a lot of books and I don’t feel the need to write essays about them. To be fair, they aren’t all this great, but I also had a new experience while reading this. I’ve never been one to get upset over the passing of famous strangers. The only famous death I’ve ever felt anything about was Carrie Fisher. (As much as I adore Joan Didion, I think she was ready. I just get a feeling she went peacefully.) Knowing Denis Johnson died in 2017 as I read this novel, well frankly: it just broke my heart. I have a really hard time connecting with people. I’m not a very relatable person; my life is both small and unconventional. The fact that there was someone out there in the world whose references, style, and philosophical obsessions matched my own so closely, and he was writing these beautiful words, and now he won’t write any more words. I can’t ask him about Already Dead, I can’t ask him if he’s ever really been to Weaverville, a teeny little town he features in the book, its population less than 1,500. I spent every childhood holiday in the car driving hours north up to The Trinity Alps. We always did our last stop in Weaverville because it was the last little town before civilization ended completely.

I remember Johnson’s death, I noted it and was sad, but after reading this novel that was so hated upon its release, that has been so thoroughly forgotten and ignored by the culture at large, I’m crushed. I’m crushed that something so unique wasn’t appreciated in its time. This book feels like a genuine expression of Johnson’s own cosmology and it wasn’t mentioned in a single obituary or profile of him after his death, at least not that I could track down. It’s not even really on his wikipedia, you have to scroll pretty far down and even then, it’s a tiny hyperlink. I think Already Dead was ahead of its time and if it were published now, it would be hugely popular. Much of the criticism it got was for its nonlinear storytelling, shifting points-of-view, and abstract use of words and punctuation. I think readers are a lot more open to experimental novels now than they were thirty years ago. Other criticisms were for the content: too much violence, too much philosophy, too much stream of consciousness-style writing, but those are all more popular now, are they not? Over the last three decades, I think most of us have become far more interested and comfortable with both philosophy and violence in our entertainment. We crave it, in that specific combination, because in fiction, violence without an underpinning philosophy is just violence. And there’s nothing profound about that. I’m thinking of a famous quote, “All that blood was never beautiful. It was just red.”1

But hey, what do I know? I’m just a girl with a myth where my head should be.

Kait Rokowski,

This was a wonderful read! I love personal essays about art/literature, and this one was top tier for me!

“The Gothic is the bloody metaphysics of the pumping human heart made decipherable, all that’s felt within our flesh and guts and our subconscious. We have so little control over these things…” pow